Is it an ignorant and selfish exercise of privilege to ignore what’s in the news or is it a self-care practice to ease mental health and just get through the day steering more into absurdism than nihilism? I find myself going back and forth on this, but more often landing in the latter camp. I’m admittedly very privileged to live where and when and how I live. I’m also very privileged to have a partner that challenges me to form opinions and take stances. But there are things happening in this world every day that cannot be ignored or denied. Stories that cannot lay buried. No matter where, when, or how in the world there is a story, journalists seek to find and expose the truth. And some seek to draw them too.

Comics journalism or visual reportage or graphic journalism (she goes by a lot of names okay?) is defined by its juxtaposition of text and images that tell a timely, reported, nonfiction story. It’s not satirical political cartoons nor does it garner its audience and sympathy from quick and volatile headlines, but with deeper, long form reporting. The secret sauce: without the artwork, the story is incomplete.

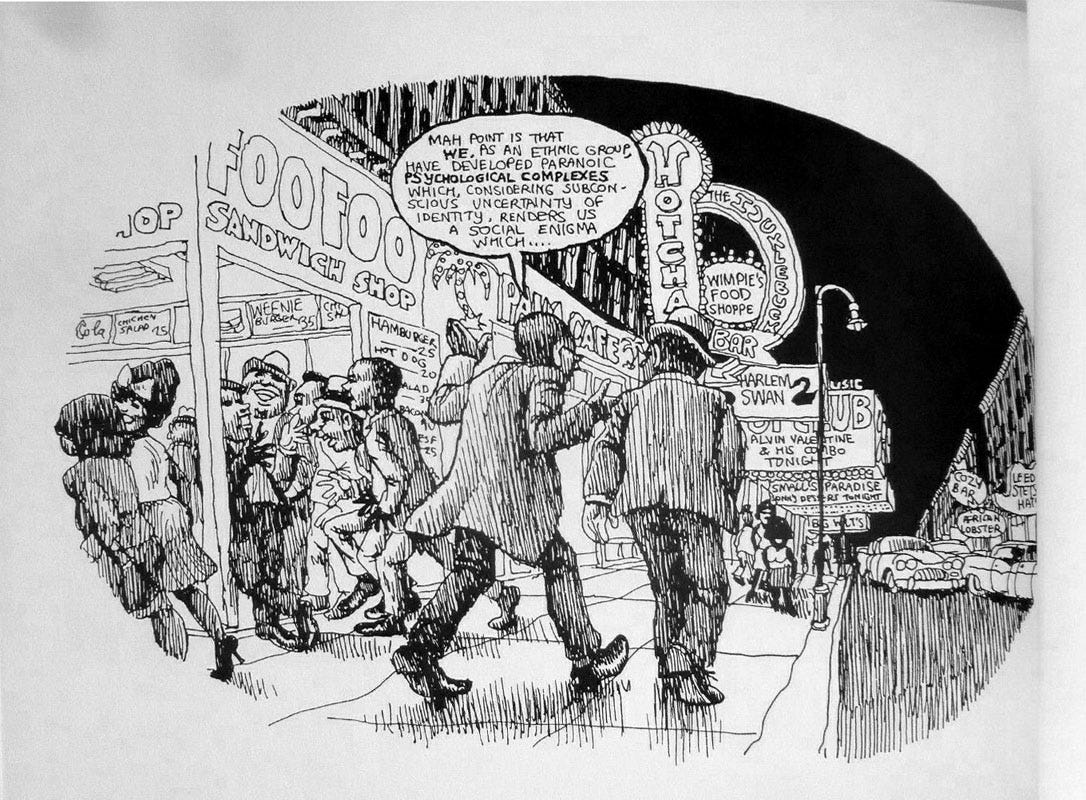

During the Civil War, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly published illustrated accounts of battles. Other times, they’d send artists to courtrooms for visual reporting. Before the proliferation of photography in print, people were drawing their accounts. In the 1920’s, New Masses, sent cartoonists to cover labor strikes. In the 50’s and 60’s, underground comix creators found work with major publications and even founded the underground comix movement through reporting on things from socialist Bulgaria to Harlem. In 1992, Art Spiegelman won the Pulitzer Prize for his graphic Holocaust memoir, Maus, and graphic novels gained overnight literary clout.

Over the years, graphic journalism has garnered Eisner and Harvey Awards. In 2022, much to the chagrin of the waning newspaper cartoonist population, the Pulitzer Prize category for Editorial Cartooning was replaced by one for Illustrated Reporting and Commentary.

To me, graphic journalism’s strength lies in its ability to convey what film and print can’t on their own. Whatever you can see or photograph can be drawn in a style that evokes symbolism and emotion. Because the reader controls the pace in a comic, cartoonists utilize innovative ways of wrapping text up in the imagery and forcing the eye to take in all the important details. In graphic journalism, everything is rendered in the cartoonist’s perspective and can’t help but lay bare their biases. And one of the best examples of this is in Joe Sacco’s Palestine.

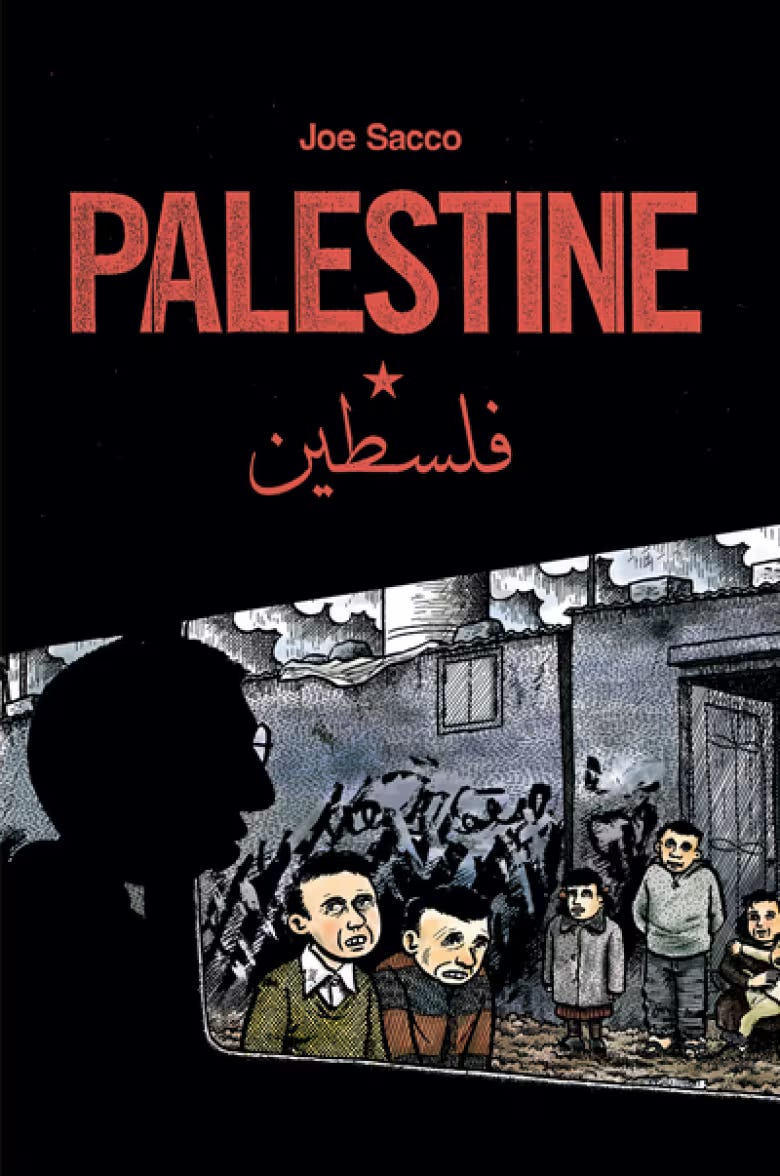

Sacco, a Maltese-American cartoonist and journalist, widely regarded as a trailblazer of graphic journalism, documented his two-month stay in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Palestine, Sacco’s debut graphic novel, is packed with stories about the people he met along the way who’ve been uprooted and displaced by the Israeli government. But it’s also packed with thrilling visual experiments that serve as testament to his efforts to forge a new journalistic path that would lead him to coin the term “comics journalism”.

[Back then] doing a book about the Palestinians was almost a fantasy project for me, in that I felt I had to do it—but I didn’t think really think anyone was going to read it. And hardly anyone did read it when it came out as a series; the sales just got lower and lower and lower. It was only when it came out as a book and the non-comics world saw it, that it started to do well. Now people are giving my work the time of day because it’s in comics form.In other words, they’re probably not going to read another book about the Palestinians. But if I do another book about the Palestinians, I know there are going to be people who are going to read it because of the fact that it is a comic. Go figure that.

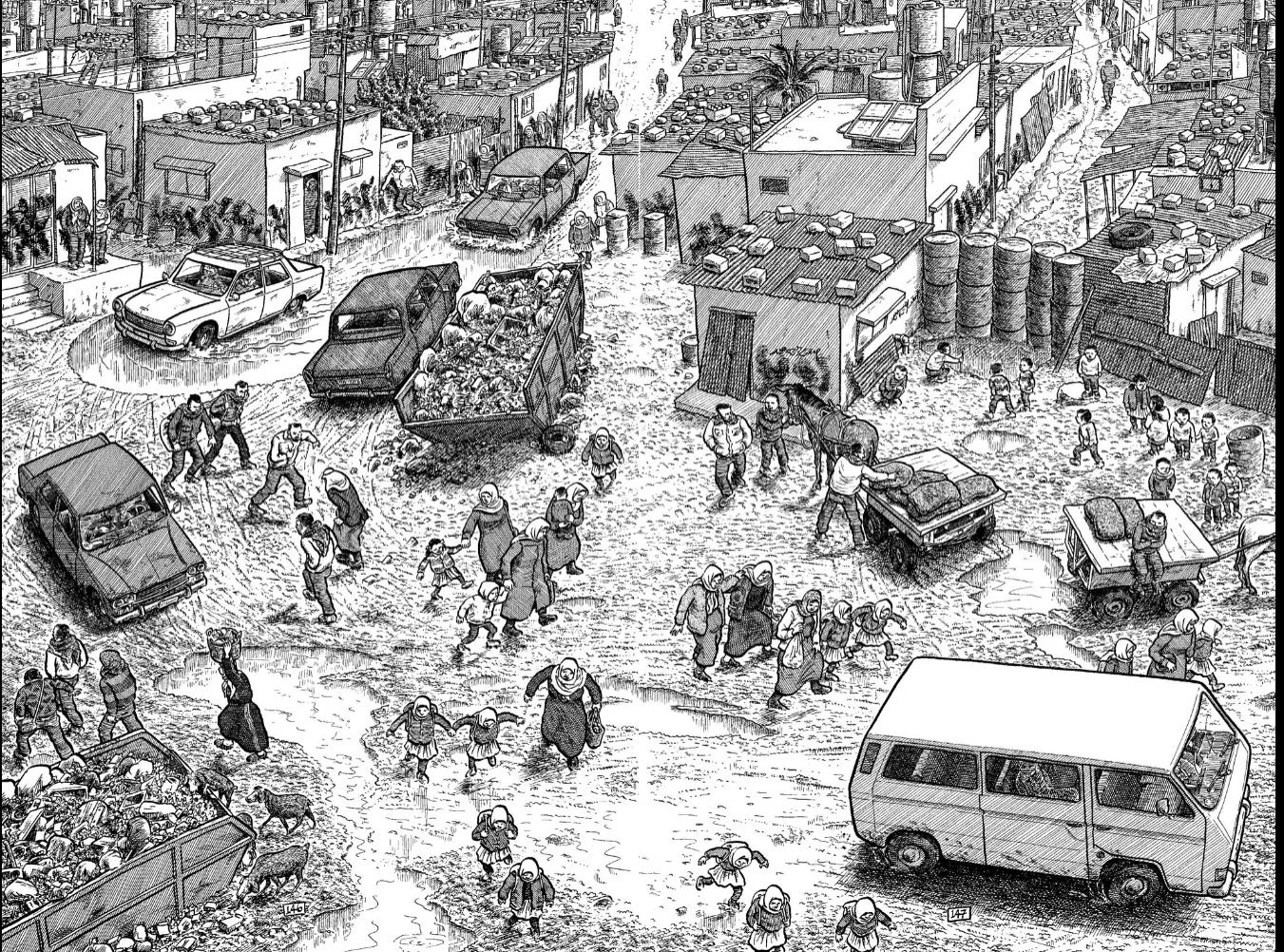

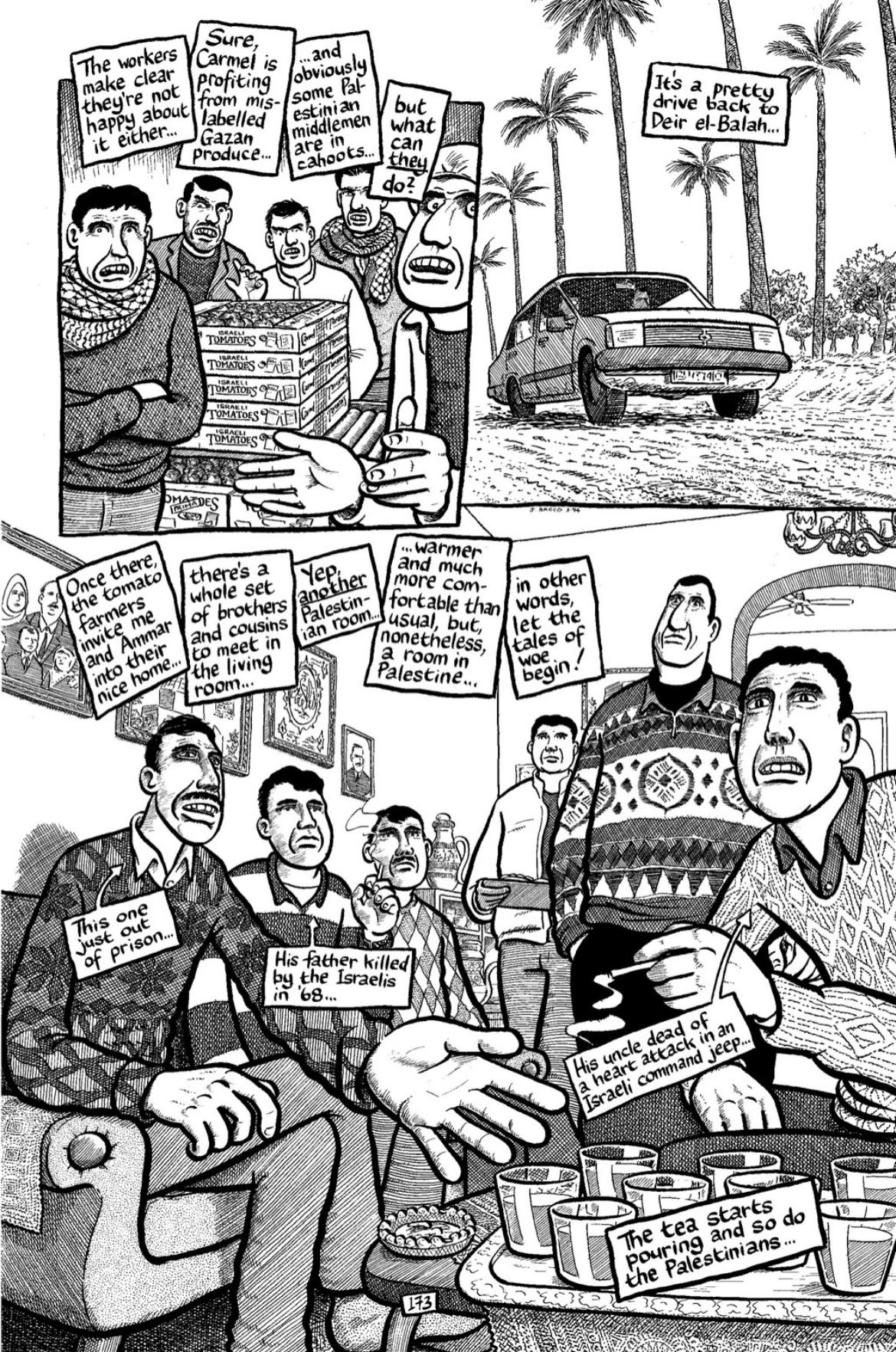

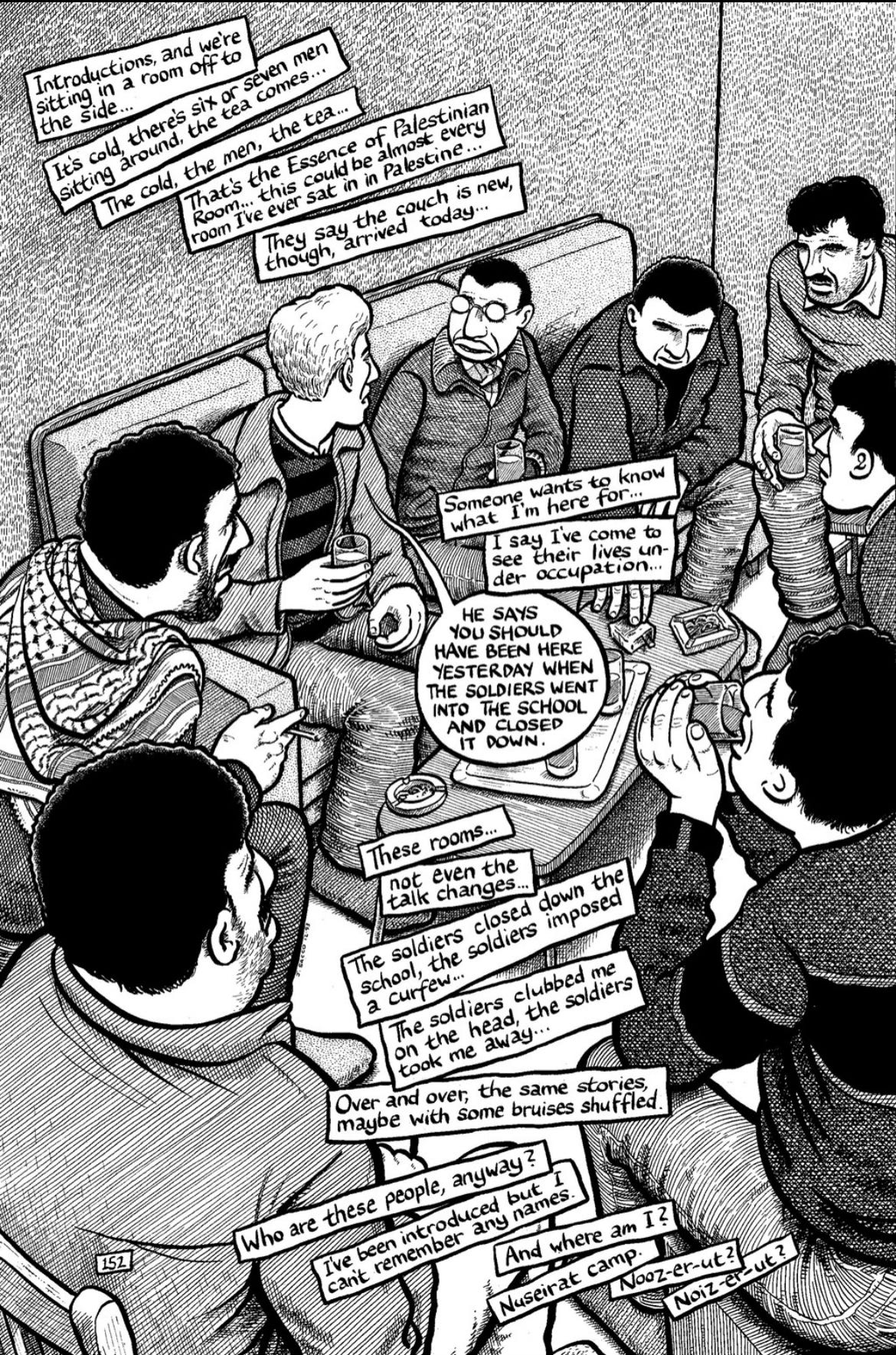

Sacco’s cartooning is extremely distinct. He has a way of portraying so much emotion and true to life details with over-exaggerated features, proportions, and scale. His depiction of himself is even kind of goofy to look at at first, but you can start to see that while the people in his book don’t appear photo-realistic, that actually makes them more relatable, more like someone on which anyone can imprint.

There is an empathy in Sacco’s work that can’t help but come through. Often throughout the book he is learning in real time proper etiquette, language, and customs in a way that is easily digestible for anyone mildly curious how Palestinians live. After being ushered around to this town and that camp, Sacco talks about how he sat in different versions of the same Palestinian room. A bunch of men huddled around, cold, drinking bottomless cups of tea and or coffee. And every room brought with it similar and horrifying stories of colonization and genocide.

Through excruciating detail and visceral visual storytelling, Sacco paved the way for graphic journalism to evolve into its current form. In recent years, several wonderful comics journalism books have been gaining attention through the Eisner Awards.

Last year alone saw Invisible Wounds: Graphic Journalism by Jess Rufflison, which recounts first hand experience from varying military personnel in a poignant and gut wrenching graphic novel. Additionally, Nellie Boy’s original news story regarding her undercover exposé in a sanitarium was adapted last year into Ten Days in a Madhouse to critical acclaim. But I love stories that uncover the true history that we aren’t taught in schools. For that I highly recommend The Black Panther Party: A Graphic History, by David F. Walker and Marcus Kwame Anderson.

Whether you follow every media outlet on TV, social media or through your local comic shop or library, there are truly remarkable stories out there of human struggling, triumph, and everyday living that deserve more attention and action.